Stories From The Road

I. Introduction

I began attending Los Angeles City College in September 1958. Although it was tuition-free and existed primarily for those who couldn’t afford or didn’t qualify for a university, the caliber of the faculty and students in the music department would have been high even at a conservatory. Among my classmates were David Breidenthal and Michele (Bloch) Zukovsky, who became principal players in the Los Angeles Philharmonic; Don Prell, then the bassist with the Bud Shank Quartet, eventually a member of the San Francisco Symphony; Horace Tapscott, Les McCann and Jimmy Woods, who all became prominent on the jazz scene; Harold Budd, "the father of ambient music," an innovative composer who was a jazz drummer in those days; Dick “Slyde” Hyde, a successful studio trombonist; David Angel, whose comprehensive musical knowledge astonishes me to this day; Ron Gorow, a brilliant orchestrator and trumpet player; Ronny Starr, a fantastic tenor saxophone player; Don Peake, a successful studio guitarist and film composer; and many others of similar ability. The faculty included Leonard Stein, who had been Arnold Schoenberg’s teaching assistant at UCLA in the 1940s and who worked with Schoenberg in preparing Structural Functions of Harmony; Hugo Strelitzer, who had been an assistant to Richard Strauss and had worked at the Berlin Opera until he was found guilty of Conducting While Jewish; Eric Zeisl, a composer who had had the same trouble as Strelitzer; Anita Priest, an organist and specialist in early music who never lost her enthusiasm for new music; and Bob McDonald, who in the 1940s had established a college credit course, perhaps the first, for jazz band. Unfortunately, McDonald left just as I was getting there although I was able to study with him later. There were other fine teachers as well (Endicott Hanson, a counterpoint teacher and Elizabeth Mayer, who taught sight-singing and dictation were excellent) and really only two, a singing teacher named Ralph Peterson, and McDonald’s replacement, Robert Wilkinson, that were not up to the level of the others. Years after the fact, Peterson was still trying to justify his refusal to allow George London, later a star at the Metropolitan Opera, to join the school chorus. Eventually, Wilkinson moved into the administration and McDonald returned to straighten things out.

Many of my classmates had returned from military service and were living on the small stipend the G.I. Bill provided. Some had already worked professionally. My problem was that as an inexperienced and somewhat less talented student, it was hard to get into the ensembles. I didn’t qualify for any of the four clarinet positions in the school orchestra. There were two jazz bands, the second of which had two saxophone sections and in my second semester I was allowed to play second alto saxophone in the second section of the second band. I did a lot of sitting and listening and only a little playing. During the summer there was only one band and, after a few people dropped out, only six saxophones, so my opportunities increased.

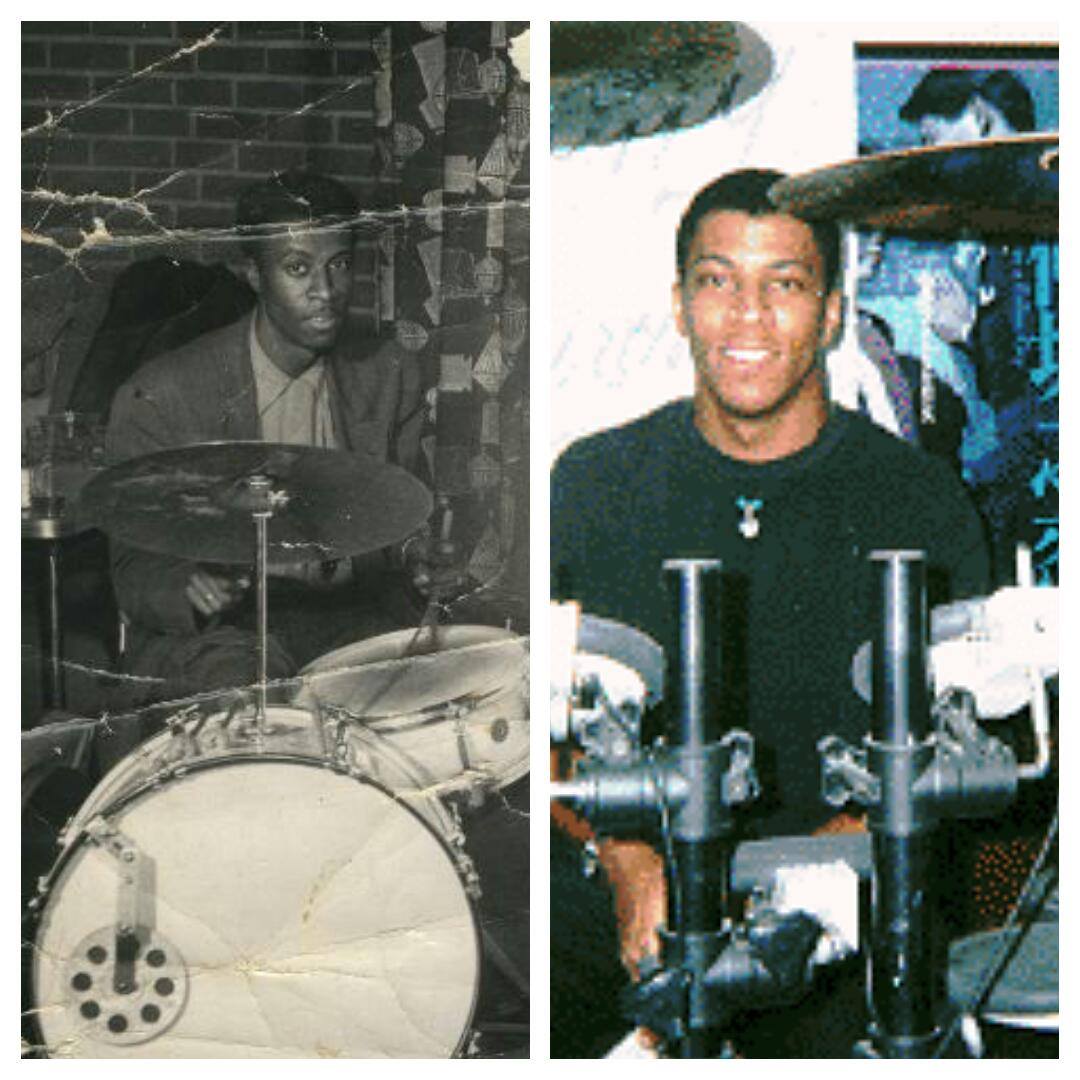

Two of the six, Allen Fischer and Jimmy Woods, shared the baritone chair. Jimmy sat quietly until it was his turn and then practically turned the room inside out with a solo that was absolutely fantastic--on a baritone saxophone he had checked out of the school’s band room. Later Jimmy would make recordings with Elvin Jones, Harold Land, Chico Hamilton and Andrew Hill. When asked how he had learned to play like that, he answered, “I was in the Air Force Band.” We probably should all have enlisted.

Allen Fischer was a funny sort of guy who never quite seemed to be in the same conversation as the person he was talking to. But one day during a break he told me that a band based in Oklahoma was looking for a tenor saxophone player. I thought about my situation at school and how the opportunity to play more might accelerate my progress and asked him how I could get in touch with the bandleader. He told me to write to him care of the “Cinerama” Ballroom, which turned out to be the Cimarron Ballroom, in Tulsa. I sent the letter off the next day.

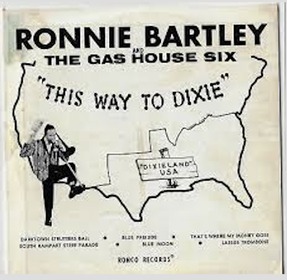

Then nothing. Through the rest of August and on into the new semester, I didn’t hear back. Days got shorter and the bus ride home seemed to get longer and gloomier and still nothing. I thought about how the letter hadn’t really said that much because in fact I hadn’t done that much: lessons with a couple of reputable teachers, gigs with a few passable local bands, but nothing like real professional experience. Then, on Thursday, January 28, 1960, Ronnie Bartley called. He offered me the “jazz tenor” chair (in fact the only tenor chair) at $75 a week. He said he would pay half the plane fare and that I would have to be there the following Tuesday. My father got on the phone and explained that he didn’t want his son around men who drank and Bartley assured him that he didn’t allow drinking on the band, the first of many alternative-reality pronouncements (aka “lies”) by the leader of one of the last three territory bands in existence. (The others were lead by Chuck Cabot, who was the brother of Johnny Richards, the famous arranger, and Ernie Fields, whose hit record the previous year had elevated him out of the territory band category after nearly 30 years of trying.) I went to school the next day to drop out. Dropping out only involved filing some papers, but I went to Leonard Stein’s harmony class to tell him in person. I had been one of the few who managed to get along with Leonard and I dreaded telling him I was leaving. “I’ll be gone for a semester, maybe a year,” I said, although I had actually decided that this was going to be my career--first Bartley, eventually Duke or Basie. “Why just a semester,” he said, “why not forever?” Next, I went downtown to Lockie Music to buy a tenor saxophone.

II. Ronnie Bartley "Winter Varieties"

From the journal I kept:

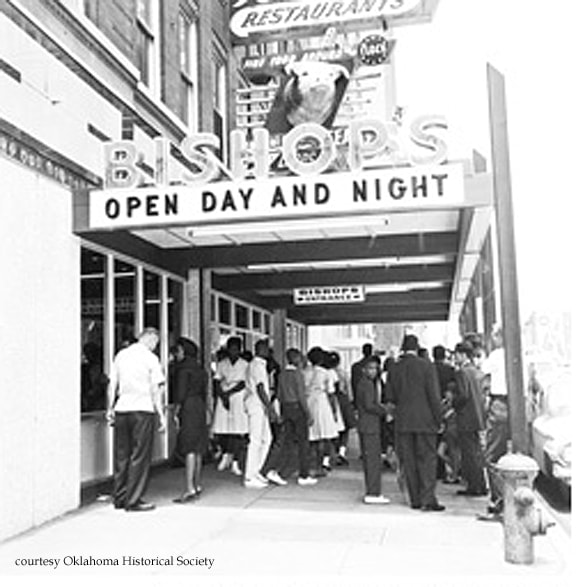

On Tuesday, February 2, 1960, I boarded an airplane for the first time in my life and walked to Tulsa, back and forth between my seat and the restroom. Walked? Wobbled is probably more like it. Bartley and his wife, Susan, met me at the airport. He was kind of hunched over and had a stiff leg. He appeared to be considerably older than his wife, who was tall and unusually blond and spoke with some kind of fake accent--as if she were trying to sound cultured. We rode in their battered VW to Bishop’s Restaurant. “It’s where the businessmen eat,” Bartley said. He recommended the Fiesta Burger and then told the waitress, “put mine and Susan’s on one check.” After dinner, he told me about a couple of hotels and suggested that I could also sleep on the bus. The American Hotel was a dollar a night, the Eagle a dollar twenty-five. I chose the bus, which was parked at a truck stop a few blocks from the restaurant.

The bus was old and cold and dirty. It had two rows of passenger seats and two triple bunks on each side and a compartment in the rear that the Bartleys used on the road. The blanket I had brought was no match for the cold. It was all pretty demoralizing. I finally managed to fall asleep, but was awakened by the sound of someone pounding on the door and yelling for me to let him in. I climbed down from my bunk. The floor was like ice. In the garish light from the truckstop sign I could see a guy in a green suit hopping from one foot to the other and swinging his arms. He swore at me and demanded that I let him in. I was still pretty groggy and asked him what time it was. He screamed, “What difference does that make...it’s 3:30.” Again he told me to open the door.

I began attending Los Angeles City College in September 1958. Although it was tuition-free and existed primarily for those who couldn’t afford or didn’t qualify for a university, the caliber of the faculty and students in the music department would have been high even at a conservatory. Among my classmates were David Breidenthal and Michele (Bloch) Zukovsky, who became principal players in the Los Angeles Philharmonic; Don Prell, then the bassist with the Bud Shank Quartet, eventually a member of the San Francisco Symphony; Horace Tapscott, Les McCann and Jimmy Woods, who all became prominent on the jazz scene; Harold Budd, "the father of ambient music," an innovative composer who was a jazz drummer in those days; Dick “Slyde” Hyde, a successful studio trombonist; David Angel, whose comprehensive musical knowledge astonishes me to this day; Ron Gorow, a brilliant orchestrator and trumpet player; Ronny Starr, a fantastic tenor saxophone player; Don Peake, a successful studio guitarist and film composer; and many others of similar ability. The faculty included Leonard Stein, who had been Arnold Schoenberg’s teaching assistant at UCLA in the 1940s and who worked with Schoenberg in preparing Structural Functions of Harmony; Hugo Strelitzer, who had been an assistant to Richard Strauss and had worked at the Berlin Opera until he was found guilty of Conducting While Jewish; Eric Zeisl, a composer who had had the same trouble as Strelitzer; Anita Priest, an organist and specialist in early music who never lost her enthusiasm for new music; and Bob McDonald, who in the 1940s had established a college credit course, perhaps the first, for jazz band. Unfortunately, McDonald left just as I was getting there although I was able to study with him later. There were other fine teachers as well (Endicott Hanson, a counterpoint teacher and Elizabeth Mayer, who taught sight-singing and dictation were excellent) and really only two, a singing teacher named Ralph Peterson, and McDonald’s replacement, Robert Wilkinson, that were not up to the level of the others. Years after the fact, Peterson was still trying to justify his refusal to allow George London, later a star at the Metropolitan Opera, to join the school chorus. Eventually, Wilkinson moved into the administration and McDonald returned to straighten things out.

Many of my classmates had returned from military service and were living on the small stipend the G.I. Bill provided. Some had already worked professionally. My problem was that as an inexperienced and somewhat less talented student, it was hard to get into the ensembles. I didn’t qualify for any of the four clarinet positions in the school orchestra. There were two jazz bands, the second of which had two saxophone sections and in my second semester I was allowed to play second alto saxophone in the second section of the second band. I did a lot of sitting and listening and only a little playing. During the summer there was only one band and, after a few people dropped out, only six saxophones, so my opportunities increased.

Two of the six, Allen Fischer and Jimmy Woods, shared the baritone chair. Jimmy sat quietly until it was his turn and then practically turned the room inside out with a solo that was absolutely fantastic--on a baritone saxophone he had checked out of the school’s band room. Later Jimmy would make recordings with Elvin Jones, Harold Land, Chico Hamilton and Andrew Hill. When asked how he had learned to play like that, he answered, “I was in the Air Force Band.” We probably should all have enlisted.

Allen Fischer was a funny sort of guy who never quite seemed to be in the same conversation as the person he was talking to. But one day during a break he told me that a band based in Oklahoma was looking for a tenor saxophone player. I thought about my situation at school and how the opportunity to play more might accelerate my progress and asked him how I could get in touch with the bandleader. He told me to write to him care of the “Cinerama” Ballroom, which turned out to be the Cimarron Ballroom, in Tulsa. I sent the letter off the next day.

Then nothing. Through the rest of August and on into the new semester, I didn’t hear back. Days got shorter and the bus ride home seemed to get longer and gloomier and still nothing. I thought about how the letter hadn’t really said that much because in fact I hadn’t done that much: lessons with a couple of reputable teachers, gigs with a few passable local bands, but nothing like real professional experience. Then, on Thursday, January 28, 1960, Ronnie Bartley called. He offered me the “jazz tenor” chair (in fact the only tenor chair) at $75 a week. He said he would pay half the plane fare and that I would have to be there the following Tuesday. My father got on the phone and explained that he didn’t want his son around men who drank and Bartley assured him that he didn’t allow drinking on the band, the first of many alternative-reality pronouncements (aka “lies”) by the leader of one of the last three territory bands in existence. (The others were lead by Chuck Cabot, who was the brother of Johnny Richards, the famous arranger, and Ernie Fields, whose hit record the previous year had elevated him out of the territory band category after nearly 30 years of trying.) I went to school the next day to drop out. Dropping out only involved filing some papers, but I went to Leonard Stein’s harmony class to tell him in person. I had been one of the few who managed to get along with Leonard and I dreaded telling him I was leaving. “I’ll be gone for a semester, maybe a year,” I said, although I had actually decided that this was going to be my career--first Bartley, eventually Duke or Basie. “Why just a semester,” he said, “why not forever?” Next, I went downtown to Lockie Music to buy a tenor saxophone.

II. Ronnie Bartley "Winter Varieties"

From the journal I kept:

On Tuesday, February 2, 1960, I boarded an airplane for the first time in my life and walked to Tulsa, back and forth between my seat and the restroom. Walked? Wobbled is probably more like it. Bartley and his wife, Susan, met me at the airport. He was kind of hunched over and had a stiff leg. He appeared to be considerably older than his wife, who was tall and unusually blond and spoke with some kind of fake accent--as if she were trying to sound cultured. We rode in their battered VW to Bishop’s Restaurant. “It’s where the businessmen eat,” Bartley said. He recommended the Fiesta Burger and then told the waitress, “put mine and Susan’s on one check.” After dinner, he told me about a couple of hotels and suggested that I could also sleep on the bus. The American Hotel was a dollar a night, the Eagle a dollar twenty-five. I chose the bus, which was parked at a truck stop a few blocks from the restaurant.

The bus was old and cold and dirty. It had two rows of passenger seats and two triple bunks on each side and a compartment in the rear that the Bartleys used on the road. The blanket I had brought was no match for the cold. It was all pretty demoralizing. I finally managed to fall asleep, but was awakened by the sound of someone pounding on the door and yelling for me to let him in. I climbed down from my bunk. The floor was like ice. In the garish light from the truckstop sign I could see a guy in a green suit hopping from one foot to the other and swinging his arms. He swore at me and demanded that I let him in. I was still pretty groggy and asked him what time it was. He screamed, “What difference does that make...it’s 3:30.” Again he told me to open the door.

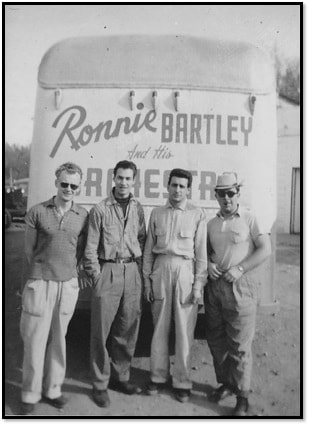

About six years before I joined the band. Jim Serpico, trumpet, is wearing a hat. The others are unidentified.

Photo courtesy of Phil Serpico.

About six years before I joined the band. Jim Serpico, trumpet, is wearing a hat. The others are unidentified.

Photo courtesy of Phil Serpico.

I asked him who he was and he said that he was the new trumpet player and again demanded to be let onto the bus. Bartley hadn’t said anything about a new trumpet player. In fact he gave me the combination to a lock that secured the front door and told me to lock it from the inside and not to let anyone in. But the guy looked pretty harmless and it was cold outside; I opened the door.

His name was Art Athey; he was 23 but looked a lot older, and he had been on the road since he was 17. For the past several months he had been working at a club in Galveston. He was from New Kensington, PA, near Pittsburgh. He asked how old I was and where I was from and if this was my first road gig. When I said yes to the road gig question he said, “That’s what I figured.”

I woke up to the sight of Artie (he said to call him that) sitting with his legs dangling over the front of the bunk, wearing a pair of boxer shorts. He was holding a hypodermic needle. He asked if he could use my belt. I didn’t know what to say. I sat there staring at him. My father had forgot to ask if there were any heroin addicts on the band. He waited a while and then laughed and told me that he was diabetic.

We walked three blocks through ice and slush and found the Denver Cafe and went inside. Artie didn’t even look at the menu. “I’ll take the ham and eggs,” he told the waitress, “eggs over easy, white toast and coffeeda drink. Is it toast or fried bread; I don’t want fried bread.” He turned to me and said, “A lot of these places give you fried bread, call it toast.” The waitress assured him they had a toaster.

He asked me if I had met Bartley. Evidently there was a territory band grapevine because he told me about Susan’s “audition.” Susan, who was eighteen at the time (four years earlier), met Bartley after the band had played a dance in the small town in Montana where she lived. She went to visit him that night and the next morning was the new band vocalist.

He repeated what Bartley had told me about the itinerary, that the band was going to New York to play at the Roseland Ballroom. He said that the Roseland gig paid $125 a week. I asked him if Bartley had to pay more than the salary we had agreed on. Artie said, “He won’t want to but the New York local will make him.” He asked my salary and I hesitated. He told me he was making $75 a week and I told him I was too.

His name was Art Athey; he was 23 but looked a lot older, and he had been on the road since he was 17. For the past several months he had been working at a club in Galveston. He was from New Kensington, PA, near Pittsburgh. He asked how old I was and where I was from and if this was my first road gig. When I said yes to the road gig question he said, “That’s what I figured.”

I woke up to the sight of Artie (he said to call him that) sitting with his legs dangling over the front of the bunk, wearing a pair of boxer shorts. He was holding a hypodermic needle. He asked if he could use my belt. I didn’t know what to say. I sat there staring at him. My father had forgot to ask if there were any heroin addicts on the band. He waited a while and then laughed and told me that he was diabetic.

We walked three blocks through ice and slush and found the Denver Cafe and went inside. Artie didn’t even look at the menu. “I’ll take the ham and eggs,” he told the waitress, “eggs over easy, white toast and coffeeda drink. Is it toast or fried bread; I don’t want fried bread.” He turned to me and said, “A lot of these places give you fried bread, call it toast.” The waitress assured him they had a toaster.

He asked me if I had met Bartley. Evidently there was a territory band grapevine because he told me about Susan’s “audition.” Susan, who was eighteen at the time (four years earlier), met Bartley after the band had played a dance in the small town in Montana where she lived. She went to visit him that night and the next morning was the new band vocalist.

He repeated what Bartley had told me about the itinerary, that the band was going to New York to play at the Roseland Ballroom. He said that the Roseland gig paid $125 a week. I asked him if Bartley had to pay more than the salary we had agreed on. Artie said, “He won’t want to but the New York local will make him.” He asked my salary and I hesitated. He told me he was making $75 a week and I told him I was too.

Rehearsal was at one o’clock at the Cimarron. The Marquee said “Tonight: The Tulsa Over Twenty-Nine Dance Club--Ronnie Bartley Orchestra. Artie introduced himself to Bartley, who pointed to the band room and told us each to get a chair and a music stand. I carried the chair and stand back to the stage and Bartley told me to sit to the right of the alto player, a big guy with blond hair and red cheeks. He said his name was Lee Naasz and then spelled it for me, pausing between the last two letters. I was introduced to the others, Don Hooker, drums, Richard Stevens, piano, and Harold Boyce, trumpet. The baritone player, Willy Coleman was sick, Bartley told us, and would not be at the rehearsal.

The rehearsal began with an arrangement of “Hawaiian War Chant” which had a vocal about fat warriors. I mumbled my part. Bartley waved to us to stop and looked at me.

“Now this isn’t the kind of band where you just play your horn,” he said. “I want to hear you sing.” He counted it off again and I joined in. We rehearsed a few more tunes and ran down the show, which we would play on the road but not at the Cimarron. After the rehearsal, Bartley told me to meet him in the band room, where he handed me a red jacket and a red bow tie.

“I’ll have to charge you something for the uniform,” he said, “so we’re even for the plane fare. The gig’s at nine tonight--be here a little early. And don’t mention our financial arrangements to the other guys.”

If I’m not careful I’m going to owe him money at the end of the week.

The rehearsal began with an arrangement of “Hawaiian War Chant” which had a vocal about fat warriors. I mumbled my part. Bartley waved to us to stop and looked at me.

“Now this isn’t the kind of band where you just play your horn,” he said. “I want to hear you sing.” He counted it off again and I joined in. We rehearsed a few more tunes and ran down the show, which we would play on the road but not at the Cimarron. After the rehearsal, Bartley told me to meet him in the band room, where he handed me a red jacket and a red bow tie.

“I’ll have to charge you something for the uniform,” he said, “so we’re even for the plane fare. The gig’s at nine tonight--be here a little early. And don’t mention our financial arrangements to the other guys.”

If I’m not careful I’m going to owe him money at the end of the week.

Lee Naasz

Lee Naasz

Artie and I had dinner at Bishop’s, the restaurant the Bartleys had taken me to last night. We sat at the counter in the front room and when the waitress smiled and said, “Hi, I’m Darlene,” Artie said, “Hi, I’m Artie” and made a grab for her hand, sending a metal napkin holder clattering to the tile floor. By the end of dinner he had completed the entire cycle: acquaintance, friendship, love and rejection. When she turned down his request for a date, he swore to her that he would never eat there again.

The gig went well. The band is pretty good, except for Susan, who sings out of tune and whose bass playing seems guided more by random chance than by any considerations having to do with tempo, meter, chord changes or key. The charts are pretty simple and a lot of them are old fashioned. A few of the more modern ones sound as if they were written for a larger group. There are occasional jazz solos for Lee, Harold or me. Rick Cox, a high school music teacher, filled in for Willy.

At 1:45 AM, forty-five minutes after the gig had ended, Bartley drove the bus a few blocks from the ballroom and double-parked in front of a hotel. He and Harold went inside and came out a few minutes later dragging a little old man. He was singing and laughing. They put him into the bunk below Artie’s. Susan said “Hello, Willy” and he grinned and waved at her and passed out. Harold went back into the hotel and came out with a suitcase. He took the wheel and Ronnie and Susan went to the compartment at the rear of the bus.

By 10:30 the next morning, somewhere between Tulsa and Roswell New Mexico, everyone was awake. Richard spanned the narrow aisle, braced himself between two seats and pedaled his feet in the air. Then he went into the wheel well (right below a sign, left over from the long ago days when the bus worked for Continental Trailways, that said “Passengers Must Remain Behind The White Line”) and stood on the second step, where he remained motionless for the next several hours. Willy’s eyes were closed and his head rolled from side to side and bounced against the metal rail above the back of his seat. Susan put a pillow behind his head. He tried to thank her; his lips moved but no sound came out. Don Hooker lay on his bunk and stared at the ceiling.

Bartley replace Harold behind the wheel. Susan stood in the aisle and Artie sprang from his seat, bowed, and offered it to her, lowering his eyes and smiling a Mona Lisa smile. Susan thanked him, excused herself, and went to the compartment in the rear.

Lee has his own way of pronouncing words, like “saze” for “says” and “fleegle horn” for “flugel horn."

***

The gig went well. The band is pretty good, except for Susan, who sings out of tune and whose bass playing seems guided more by random chance than by any considerations having to do with tempo, meter, chord changes or key. The charts are pretty simple and a lot of them are old fashioned. A few of the more modern ones sound as if they were written for a larger group. There are occasional jazz solos for Lee, Harold or me. Rick Cox, a high school music teacher, filled in for Willy.

At 1:45 AM, forty-five minutes after the gig had ended, Bartley drove the bus a few blocks from the ballroom and double-parked in front of a hotel. He and Harold went inside and came out a few minutes later dragging a little old man. He was singing and laughing. They put him into the bunk below Artie’s. Susan said “Hello, Willy” and he grinned and waved at her and passed out. Harold went back into the hotel and came out with a suitcase. He took the wheel and Ronnie and Susan went to the compartment at the rear of the bus.

By 10:30 the next morning, somewhere between Tulsa and Roswell New Mexico, everyone was awake. Richard spanned the narrow aisle, braced himself between two seats and pedaled his feet in the air. Then he went into the wheel well (right below a sign, left over from the long ago days when the bus worked for Continental Trailways, that said “Passengers Must Remain Behind The White Line”) and stood on the second step, where he remained motionless for the next several hours. Willy’s eyes were closed and his head rolled from side to side and bounced against the metal rail above the back of his seat. Susan put a pillow behind his head. He tried to thank her; his lips moved but no sound came out. Don Hooker lay on his bunk and stared at the ceiling.

Bartley replace Harold behind the wheel. Susan stood in the aisle and Artie sprang from his seat, bowed, and offered it to her, lowering his eyes and smiling a Mona Lisa smile. Susan thanked him, excused herself, and went to the compartment in the rear.

Lee has his own way of pronouncing words, like “saze” for “says” and “fleegle horn” for “flugel horn."

***

Roswell, New Mexico. Roy’s Rancho has a hitching rail, latticed swinging doors and bartenders in cowboy hats.

The first set was dance music but some hipper charts than the other night in Tulsa. At the end of the set, Hooker played a drum roll and cymbal crash and Bartley announced that we would be back with “our all new show, Winter Varieties of 1960.”

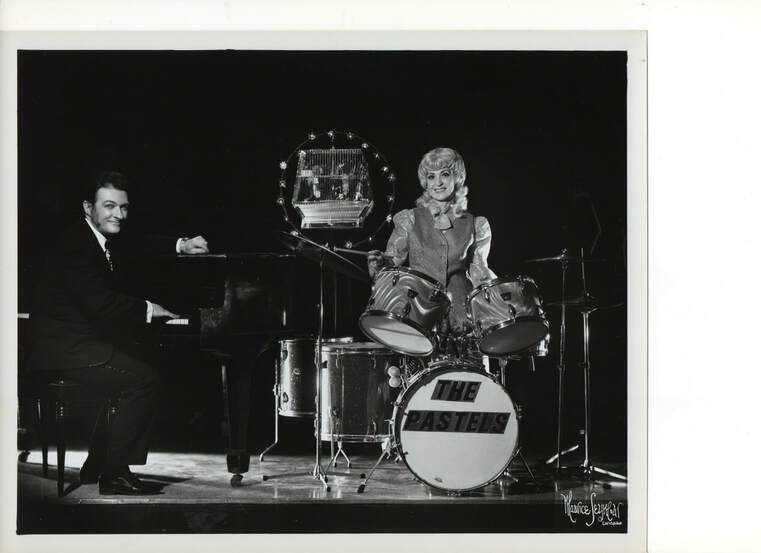

The show began with a salute to the big bands. We (all nine of us) played “Let’s Dance” (Benny Goodman), “Boo Hoo” (Guy Lombardo), “Getting Sentimental Over You” (Tommy Dorsey), “Moonlight Serenade” (Glenn Miller), “Contrasts” (Jimmy Dorsey) and “Bubbles In The Wine (Lawrence Welk) with Richard playing the accordion. Bartley told some jokes and then said, Let’s hear it for Miss Personality, Susan Gray,” and Susan entered. She had changed from a gold sequined dress to a leotard under a wrap-around skirt. Pretty makeshift, even for a vestigial territory band at a cowboy bar in Roswell.

She sang “Bye-Bye Blackbird” and then took off the skirt and did a dance, the same step over and over, hopping back and forth across the front of the bandstand. She left and Bartley urged the audience to “bring her back for an encore.” She barely made it to the microphone before what little applause there was died and sang “Put The Blame On Mame.” Next was “Jumpin’ At The Woodside” in which each of us played a solo while Bartley announced our names and home towns. (He said I was from Hollywood; I guess Culver City just didn’t have the right ring to it.) The show ended with “When The Saints Go Marchin’ In.” Bartley played a solo operating the slide with his foot and lost two measures. Lee told me it happened every night.

After the show, I went to the bar with Lee and Artie. I gave Lee a quarter and he bought me a beer. Artie was worried. “Bartley keeps looking at me,” he said. “I think he’s going to fire me.”

Lee tried to reassure him. “Don’t worry,” he said. “There’s not that many cats that’ll work for this kind of bread.”

Richard, an excellent pianist, says he is not really a pianist at all; his real instrument is the clarinet and he is the new Artie Shaw. He has one clarinet solo in the book, his own (bad) arrangement of “Begin The Beguine.” Tonight, he surrounded the melody with a lot of squeaks and squawks. Lee said it went better than usual. Richard is a religious fanatic. He has curly blond hair, unusually short arms and an unpleasant aroma.

We spent the night on the bus, at a truck stop a few miles from the gig.

The first set was dance music but some hipper charts than the other night in Tulsa. At the end of the set, Hooker played a drum roll and cymbal crash and Bartley announced that we would be back with “our all new show, Winter Varieties of 1960.”

The show began with a salute to the big bands. We (all nine of us) played “Let’s Dance” (Benny Goodman), “Boo Hoo” (Guy Lombardo), “Getting Sentimental Over You” (Tommy Dorsey), “Moonlight Serenade” (Glenn Miller), “Contrasts” (Jimmy Dorsey) and “Bubbles In The Wine (Lawrence Welk) with Richard playing the accordion. Bartley told some jokes and then said, Let’s hear it for Miss Personality, Susan Gray,” and Susan entered. She had changed from a gold sequined dress to a leotard under a wrap-around skirt. Pretty makeshift, even for a vestigial territory band at a cowboy bar in Roswell.

She sang “Bye-Bye Blackbird” and then took off the skirt and did a dance, the same step over and over, hopping back and forth across the front of the bandstand. She left and Bartley urged the audience to “bring her back for an encore.” She barely made it to the microphone before what little applause there was died and sang “Put The Blame On Mame.” Next was “Jumpin’ At The Woodside” in which each of us played a solo while Bartley announced our names and home towns. (He said I was from Hollywood; I guess Culver City just didn’t have the right ring to it.) The show ended with “When The Saints Go Marchin’ In.” Bartley played a solo operating the slide with his foot and lost two measures. Lee told me it happened every night.

After the show, I went to the bar with Lee and Artie. I gave Lee a quarter and he bought me a beer. Artie was worried. “Bartley keeps looking at me,” he said. “I think he’s going to fire me.”

Lee tried to reassure him. “Don’t worry,” he said. “There’s not that many cats that’ll work for this kind of bread.”

Richard, an excellent pianist, says he is not really a pianist at all; his real instrument is the clarinet and he is the new Artie Shaw. He has one clarinet solo in the book, his own (bad) arrangement of “Begin The Beguine.” Tonight, he surrounded the melody with a lot of squeaks and squawks. Lee said it went better than usual. Richard is a religious fanatic. He has curly blond hair, unusually short arms and an unpleasant aroma.

We spent the night on the bus, at a truck stop a few miles from the gig.

The next morning, I woke up at 9:30. Hooker was gone. He’s real quiet and stays pretty much to himself. The others were still asleep. The front of the bus was littered with empty bottles and wrappers from packages of cheese and crackers.

I ate breakfast at the truck stop cafe and when I returned to the bus only Artie, Richard and Willy remained. Richard looked sick. Artie walked to the far end of the lot and back again, pausing to peer into the cafe before reentering the bus. He looked impatient. “Are you coming or not,” he asked Richard.

“Not.”

“You’ll feel better if you eat something,” he told him.

Richard wasn’t so sure.

“The food absorbs the alcohol,” Artie told him. “It kinda diminishes the effect. The more you eat the sooner the hangover goes away.”

Richard looked skeptical. He got up and stood unsteadily for a moment then hurtled to the restroom inside the truck stop office. Artie and I walked toward the building and waited until he came out. His head was soaked with water and there was a semblance of his normal goofy expression. “Shall we go?” he asked and tried to link arms with Artie.

Artie asked me if I had had breakfast. I told him I had.

“Where at?” he wanted to know.

I pointed to the truck stop cafe.

“Any good?”

“Yeah, it’s ok.”

“C’mon,” he said to Richard, and they walked toward town.

Back on the bus, Willy rummaged in the bunk beneath his and came up with a nearly empty vodka bottle. “Man’s best friend,” he said. He swallowed most of what was left and held the bottle out to me. I declined.

“I suppose you don’t drink,” he said. I told him it was a little too early for me.

“Well, it ain’t too early for me,” he said and winked. He finished the bottle and tacked his way to the cafe.

A car pulled up and Ronnie and Susan got out. “Where’s Richard?” Ronnie asked.

I told him he had left a few minutes earlier.

“Yeah, but where did he go?” Bartley sounded impatient or maybe a little worried. I told him I didn’t know, but that he had headed off toward town. He asked if he was alone. I told him that Artie had gone with him. He looked relieved.

“Every time he’s by himself he gets lost. I told Artie to keep an eye on him but I couldn’t tell if he took me seriously.”

The same car returned and took the Bartleys to dinner. The rest of us ate at the truckstop, Willy, Artie and Richard at one booth, Lee, Harold and I at another. Don Hooker sat at the counter and declined invitations from both camps.

At the gig, midway through the first set, Willy quit playing and began fiddling with a stuck key on his baritone. It was actually a relief when he dropped out. When he thought he had it fixed, he tried it, oblivious to the rest of us, and wound up honking a couple of notes during Lee’s solo on “Blue Skies”.

Last night, no one paid attention to the jokes. Tonight, we weren’t so lucky. One heckler was funnier than Bartley.

I ate breakfast at the truck stop cafe and when I returned to the bus only Artie, Richard and Willy remained. Richard looked sick. Artie walked to the far end of the lot and back again, pausing to peer into the cafe before reentering the bus. He looked impatient. “Are you coming or not,” he asked Richard.

“Not.”

“You’ll feel better if you eat something,” he told him.

Richard wasn’t so sure.

“The food absorbs the alcohol,” Artie told him. “It kinda diminishes the effect. The more you eat the sooner the hangover goes away.”

Richard looked skeptical. He got up and stood unsteadily for a moment then hurtled to the restroom inside the truck stop office. Artie and I walked toward the building and waited until he came out. His head was soaked with water and there was a semblance of his normal goofy expression. “Shall we go?” he asked and tried to link arms with Artie.

Artie asked me if I had had breakfast. I told him I had.

“Where at?” he wanted to know.

I pointed to the truck stop cafe.

“Any good?”

“Yeah, it’s ok.”

“C’mon,” he said to Richard, and they walked toward town.

Back on the bus, Willy rummaged in the bunk beneath his and came up with a nearly empty vodka bottle. “Man’s best friend,” he said. He swallowed most of what was left and held the bottle out to me. I declined.

“I suppose you don’t drink,” he said. I told him it was a little too early for me.

“Well, it ain’t too early for me,” he said and winked. He finished the bottle and tacked his way to the cafe.

A car pulled up and Ronnie and Susan got out. “Where’s Richard?” Ronnie asked.

I told him he had left a few minutes earlier.

“Yeah, but where did he go?” Bartley sounded impatient or maybe a little worried. I told him I didn’t know, but that he had headed off toward town. He asked if he was alone. I told him that Artie had gone with him. He looked relieved.

“Every time he’s by himself he gets lost. I told Artie to keep an eye on him but I couldn’t tell if he took me seriously.”

The same car returned and took the Bartleys to dinner. The rest of us ate at the truckstop, Willy, Artie and Richard at one booth, Lee, Harold and I at another. Don Hooker sat at the counter and declined invitations from both camps.

At the gig, midway through the first set, Willy quit playing and began fiddling with a stuck key on his baritone. It was actually a relief when he dropped out. When he thought he had it fixed, he tried it, oblivious to the rest of us, and wound up honking a couple of notes during Lee’s solo on “Blue Skies”.

Last night, no one paid attention to the jokes. Tonight, we weren’t so lucky. One heckler was funnier than Bartley.

Payday. My $75 comes to $69.64 after taxes.

Back in Tulsa, Artie and I decided to get hotel rooms. We chose the American Hotel, against Willy’s advice, because the rooms were only a dollar a night, a quarter less than the Eagle. Willy says the rooms at th’ murican are so small ya caint hardly turn round nur have viz-ters.

The entrance to the hotel was between a shoe repair shop and a taxidermist. At the top of an unlit staircase there was a tiny lobby with a worn couch, a tall lamp and an old TV set, everything covered in dust. Behind a counter, next to some mailboxes was a sign that said CHECKOUT TIME IS NOON--PAYMENT MUST BE MADE IN ADVANCE. Below the sign was a card table. A man sat at the table with his back to us. He had a teaspoon in one hand and a banana in the other. In front of him were jars of peanut butter and jelly. He balanced a spoonful of jelly on the end of the banana, studied it, and took a bite. Then he ate a spoonful of peanut butter. He repeated the sequence until the banana was gone before turning to acknowledge us. He was short and dumpy, with a receding hairline, tiny, spaced teeth and a phony smile, the Art Athey of some future time.

Artie turned white and his head began to tremble. He clutched the lapels of his jacket with quaking hands.

The clerk asked us how long we were going to be staying there. I told him two nights.

“One,” said Artie. His voice rasped, like an empty faucet.

“A buck a night in advance,” said the clerk. “Checkout time is noon.” He gave each of us a skeleton key attached to a plastic plaque and told us there were a shower and toilet at the end of each of the two parallel hallways.

My room was number seventeen. The bed had a metal frame and made noise every time I moved. The dresser was chipped and scarred and a gooseneck lamp was bolted to it. A string hung from a light in the ceiling. There was a washbasin beneath a broken mirror. The only window looked across a gravel roof to the other wing of the hotel. Wooden blocks nailed to the frame kept the window from opening more than a few inches and it was covered by a paper shade that wouldn’t retract.

Exploring Tulsa. There’s a Walgreens nearby which is better than the Denver, although a little more expensive, and a place a block from the ballroom where hamburgers are a nickel. The place is tiny--a counter with four stools--and the burgers minuscule. Everything else is regular size and price. The menu is painted on the wall and says “ME&U”.

Downtown, I found a record store. It has one jazz bin with a skimpy selection. I took a Sonny Stitt album into a listening booth but I barely made it through the first side; I guess the clerk can spot a non-buyer, because he kept staring at me until I couldn’t stand it any more and split.

***

Back in Tulsa, Artie and I decided to get hotel rooms. We chose the American Hotel, against Willy’s advice, because the rooms were only a dollar a night, a quarter less than the Eagle. Willy says the rooms at th’ murican are so small ya caint hardly turn round nur have viz-ters.

The entrance to the hotel was between a shoe repair shop and a taxidermist. At the top of an unlit staircase there was a tiny lobby with a worn couch, a tall lamp and an old TV set, everything covered in dust. Behind a counter, next to some mailboxes was a sign that said CHECKOUT TIME IS NOON--PAYMENT MUST BE MADE IN ADVANCE. Below the sign was a card table. A man sat at the table with his back to us. He had a teaspoon in one hand and a banana in the other. In front of him were jars of peanut butter and jelly. He balanced a spoonful of jelly on the end of the banana, studied it, and took a bite. Then he ate a spoonful of peanut butter. He repeated the sequence until the banana was gone before turning to acknowledge us. He was short and dumpy, with a receding hairline, tiny, spaced teeth and a phony smile, the Art Athey of some future time.

Artie turned white and his head began to tremble. He clutched the lapels of his jacket with quaking hands.

The clerk asked us how long we were going to be staying there. I told him two nights.

“One,” said Artie. His voice rasped, like an empty faucet.

“A buck a night in advance,” said the clerk. “Checkout time is noon.” He gave each of us a skeleton key attached to a plastic plaque and told us there were a shower and toilet at the end of each of the two parallel hallways.

My room was number seventeen. The bed had a metal frame and made noise every time I moved. The dresser was chipped and scarred and a gooseneck lamp was bolted to it. A string hung from a light in the ceiling. There was a washbasin beneath a broken mirror. The only window looked across a gravel roof to the other wing of the hotel. Wooden blocks nailed to the frame kept the window from opening more than a few inches and it was covered by a paper shade that wouldn’t retract.

Exploring Tulsa. There’s a Walgreens nearby which is better than the Denver, although a little more expensive, and a place a block from the ballroom where hamburgers are a nickel. The place is tiny--a counter with four stools--and the burgers minuscule. Everything else is regular size and price. The menu is painted on the wall and says “ME&U”.

Downtown, I found a record store. It has one jazz bin with a skimpy selection. I took a Sonny Stitt album into a listening booth but I barely made it through the first side; I guess the clerk can spot a non-buyer, because he kept staring at me until I couldn’t stand it any more and split.

***

On the road to Cheyenne. A few miles from the ballroom the transmission started acting up and we had to turn back. We made it back to the truck stop in second gear. Bartley left a note for the garage man and we waited in the bus while Artie drove Hooker to pick up his car. They returned shortly and Bartley made the assignments. He, Susan and Richard would ride with Hooker in his Chrysler, the rest of us in Artie’s ‘53 Plymouth.

It began to snow and just as we crossed into Colorado the heater stopped working. The temperature inside the car quickly fell below freezing. Harold scraped ice from the windshield and lit matches and held them close to Artie’s feet. I sat in the back between Willy and Lee. Willy’s face was a mosaic of tiny red and blue lines and he trembled violently.

We rode like that for hours, Harold scraping and lighting, the wiper blades scraping and groaning, Willy groaning, no one talking, listening to the snow and the engine until Artie bellowed and kicked the brake pedal with such force that the car spun around and slid to a stop in front of a gas station on the other side of the road. Harold grabbed Artie’s arm and screamed, “man what are you doing, you could have gotten us killed.”

Artie jerked free. “I know this place,” he squealed, and ran into the office. We followed him and heard his voice coming from behind a door with a sign on it that said, “KEEP OUT”. After a moment he emerged holding a paper bag and ordered us back into his car. His voice had a new authority. He drove about a quarter mile, parked by the side of the road, and pulled a pint of bourbon from the bag. “Two bucks each or you don’t get any,” he said. He drank from the bottle and handed it to Harold.

“Keep an eye on Willy,” said Harold, as he passed the bottle back to us.

The whiskey went quickly. We asked Artie why he had not bought more.

“You kiddin’, man? He didn’t want to sell me this, but I know that place, I been through here before.”

Cheyenne Wyoming. The gig was at a country club where they let us use the locker room to shower and shave and change and they gave us sandwiches and coffee.

During the break after the show, George Duncan introduced himself. Duncan is a bass player who sometimes works as a bartender. He heard Bartley announce that I was from Hollywood and wondered if I knew his old Air Force buddy, Horace Tapscott. “Taps” and I had played gigs when we were going to LACC. We talked about him for a while and I told Duncan (he said to tell Horace I had met “Uncle Duncan”) about our trip. He said he was about to junk his ‘53 Plymouth and offered us the heater. He invited us for breakfast the next morning.

Duncan and his wife live in a trailer park. She made breakfast and he played his bass for us and insisted that Susan try it out.

Naturally, once we had a working heater the weather got nicer. Artie took a different route home, through Nebraska and Kansas and for part of the time we were even able to open the window a bit.

***

It began to snow and just as we crossed into Colorado the heater stopped working. The temperature inside the car quickly fell below freezing. Harold scraped ice from the windshield and lit matches and held them close to Artie’s feet. I sat in the back between Willy and Lee. Willy’s face was a mosaic of tiny red and blue lines and he trembled violently.

We rode like that for hours, Harold scraping and lighting, the wiper blades scraping and groaning, Willy groaning, no one talking, listening to the snow and the engine until Artie bellowed and kicked the brake pedal with such force that the car spun around and slid to a stop in front of a gas station on the other side of the road. Harold grabbed Artie’s arm and screamed, “man what are you doing, you could have gotten us killed.”

Artie jerked free. “I know this place,” he squealed, and ran into the office. We followed him and heard his voice coming from behind a door with a sign on it that said, “KEEP OUT”. After a moment he emerged holding a paper bag and ordered us back into his car. His voice had a new authority. He drove about a quarter mile, parked by the side of the road, and pulled a pint of bourbon from the bag. “Two bucks each or you don’t get any,” he said. He drank from the bottle and handed it to Harold.

“Keep an eye on Willy,” said Harold, as he passed the bottle back to us.

The whiskey went quickly. We asked Artie why he had not bought more.

“You kiddin’, man? He didn’t want to sell me this, but I know that place, I been through here before.”

Cheyenne Wyoming. The gig was at a country club where they let us use the locker room to shower and shave and change and they gave us sandwiches and coffee.

During the break after the show, George Duncan introduced himself. Duncan is a bass player who sometimes works as a bartender. He heard Bartley announce that I was from Hollywood and wondered if I knew his old Air Force buddy, Horace Tapscott. “Taps” and I had played gigs when we were going to LACC. We talked about him for a while and I told Duncan (he said to tell Horace I had met “Uncle Duncan”) about our trip. He said he was about to junk his ‘53 Plymouth and offered us the heater. He invited us for breakfast the next morning.

Duncan and his wife live in a trailer park. She made breakfast and he played his bass for us and insisted that Susan try it out.

Naturally, once we had a working heater the weather got nicer. Artie took a different route home, through Nebraska and Kansas and for part of the time we were even able to open the window a bit.

***

The showers at the American Hotel are a lost cause. Water dribbles out at about the same rate whether they are on or off and there is a scum on the floor that never quite gets washed away. When we get back from Lawrence, Kansas, I’ll try the Eagle Hotel, extra quarter and all.

I went to the YMCA and asked the guy if I could pay him and take a shower. He said I could swim for the same price. I told him I didn’t have a suit and he looked funny at me and said they don’t wear suits. I paid him and had the big pool all to myself.

I have been practicing at the ballroom over the objections of the manager, Mr. Allen, who works within earshot. One day I heard him complaining to Leon McAuliffe, the owner. Leon laughed and said he wished the boys in his band would do some practicing. Whenever he sees me, Leon says “howdy”. Everyone around here says howdy, except Mr. Allen. People on the street, people I’ve never seen before, people dressed up like cowboys all say howdy.

Nights when we’re not working there is usually someone from the band at the Denver Cafe. We stay until late and drink a lot of coffee. Every once in a while they charge us for another cup. Tonight I ordered the hamburger combo and told the waitress I didn’t want beets on my salad.

“We don’t have beets,” she said, “but I can give it to you without carrots.”

***

I went to the YMCA and asked the guy if I could pay him and take a shower. He said I could swim for the same price. I told him I didn’t have a suit and he looked funny at me and said they don’t wear suits. I paid him and had the big pool all to myself.

I have been practicing at the ballroom over the objections of the manager, Mr. Allen, who works within earshot. One day I heard him complaining to Leon McAuliffe, the owner. Leon laughed and said he wished the boys in his band would do some practicing. Whenever he sees me, Leon says “howdy”. Everyone around here says howdy, except Mr. Allen. People on the street, people I’ve never seen before, people dressed up like cowboys all say howdy.

Nights when we’re not working there is usually someone from the band at the Denver Cafe. We stay until late and drink a lot of coffee. Every once in a while they charge us for another cup. Tonight I ordered the hamburger combo and told the waitress I didn’t want beets on my salad.

“We don’t have beets,” she said, “but I can give it to you without carrots.”

***

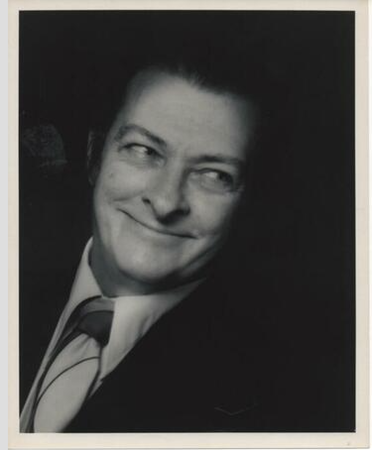

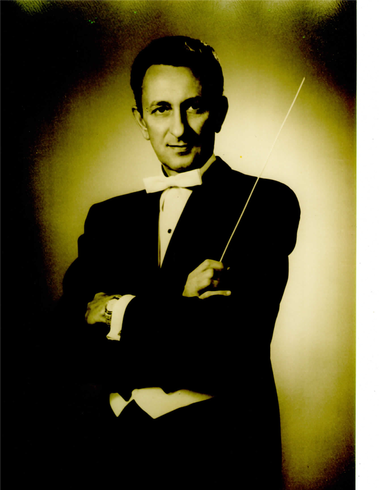

Max Waits, flutist and conductor. Max had studied with Marcel Moyse, whose name he pronounced to rhyme with "noise," instead of Mo-eese, like everyone else. Of course, Max actually knew him...

Thanks to Ron Wheeler and the Tulsa Youth Symphony Orchestra for the photo.

Max Waits, flutist and conductor. Max had studied with Marcel Moyse, whose name he pronounced to rhyme with "noise," instead of Mo-eese, like everyone else. Of course, Max actually knew him...

Thanks to Ron Wheeler and the Tulsa Youth Symphony Orchestra for the photo.

I called Max Waits, who plays in the Tulsa Philharmonic, about taking flute lessons. He sounds like a nice guy; he knows bus routes and numbers and he only charges $3 for a half hour lesson.

He wears a three-piece suit and shiny shoes and he says to call him Max. He’s friendly and he plays great. His studio at Tulsa University is more like someone’s den than a classroom. After the lesson I went downstairs to the practice rooms and heard some good players.

We played at a military base near Lawrence. Up till now Lee and Artie have been buying beer for me, but Lee said I could get if for myself here. I didn’t believe him but they sold it to me without a second glance.

We slept on the bus. Artie and I went to breakfast at the Jayhawk Cafe. The place was crowded with students and very noisy. Artie felt out of place, the green suit and all, and wanted to go somewhere else. I told him to go ahead but he decided he would rather stay there and complain. I hoped someone would start a conversation but we might as well have been invisible.

2:00 PM. Harold was driving. The Bartleys were in their room. Hooker was lying on top of his bunk looking at the ceiling. Richard was in the wheel well studying the white lines on the highway. Lee, Artie, Willy and I were in the passenger seats, Artie working on an arrangement, Lee dozing.

A billboard said “CH—CH--What’s Missing?”

“UR” said Willy.

“Amen,” said Richard.

9:00 PM. A lodge hall in Salina, Kansas. Lots of drunks. One of them got angry when Bartley said I was from Hollywood and demanded to see my i.d. I confessed that I was from Culver City, Where Hollywood Movies Are Made. Close enough, I guess; he bought Lee and me drinks and told us his brother in law plays trumpet with Guy Lombardo. After he had staggered off, Lee said, “twenty eight.” I asked him what he was talking about.

“That’s the twenty-eighth guy who’s told me his brother in law plays trumpet with Lombardo. Must be a huge band.”

***

He wears a three-piece suit and shiny shoes and he says to call him Max. He’s friendly and he plays great. His studio at Tulsa University is more like someone’s den than a classroom. After the lesson I went downstairs to the practice rooms and heard some good players.

We played at a military base near Lawrence. Up till now Lee and Artie have been buying beer for me, but Lee said I could get if for myself here. I didn’t believe him but they sold it to me without a second glance.

We slept on the bus. Artie and I went to breakfast at the Jayhawk Cafe. The place was crowded with students and very noisy. Artie felt out of place, the green suit and all, and wanted to go somewhere else. I told him to go ahead but he decided he would rather stay there and complain. I hoped someone would start a conversation but we might as well have been invisible.

2:00 PM. Harold was driving. The Bartleys were in their room. Hooker was lying on top of his bunk looking at the ceiling. Richard was in the wheel well studying the white lines on the highway. Lee, Artie, Willy and I were in the passenger seats, Artie working on an arrangement, Lee dozing.

A billboard said “CH—CH--What’s Missing?”

“UR” said Willy.

“Amen,” said Richard.

9:00 PM. A lodge hall in Salina, Kansas. Lots of drunks. One of them got angry when Bartley said I was from Hollywood and demanded to see my i.d. I confessed that I was from Culver City, Where Hollywood Movies Are Made. Close enough, I guess; he bought Lee and me drinks and told us his brother in law plays trumpet with Guy Lombardo. After he had staggered off, Lee said, “twenty eight.” I asked him what he was talking about.

“That’s the twenty-eighth guy who’s told me his brother in law plays trumpet with Lombardo. Must be a huge band.”

***

Wichita can’t be more than a hundred miles from Salina, yet it took nearly four hours over the icy roads to get to the outskirts only to have the bus break down. We couldn’t use the heater since the engine didn’t work, so we wrapped ourselves in blankets and sat in the passenger seats except for Willy, who stayed in his bunk and drank the last of his vodka, and the Bartleys, who went to their room. When it got light some of us went looking for a place to eat but before we could find anything it began to snow and we had to run back to the bus.

By 9:00 AM the weather had eased up enough so we were able to walk to town and find a restaurant. Bartley made some calls and before long a truck came and towed us to a garage. They wouldn’t work on Sunday, so we were stuck there at least a day. Bartley got a key to a side door so we could come and go but everything around the garage was closed and it was too cold to go far.

Everyone seemed to be taking the confinement in stride. Artie worked on a chart (his writing and copying were better than his playing), the others just sat around. Willy tried to push the “Coffee--Black” button on a vending machine, but his hand was too unsteady. He asked for help, but Bartley grabbed his hand--like catching a hummingbird--and with Willy’s bony index finger pushed the chicken soup button instead.

“The power of suggestion,” Bartley said.

Downtown Wichita may not be half as exciting as everyone thinks but it sure beats starving to death in a freezing garage. Lee, Artie and I went to a restaurant where Artie asked the waitress to quit her job and run away with him.

Richard made quite a hit with the mechanics. They laughed at everything he said and at his splayfooted, arm-swinging walk. They saw him as part Charlie Chaplin, part Huntz Hall. He loved the attention. He voiced one inanity after another and walked back and forth to the unending glee of the men. Finally Bartley, fearing the bus would never get fixed, ordered him to his seat. That lasted about five minutes.

Willy asked Bartley for a draw (an advance on his salary). Bartley asked why he needed the money. Willy said he was hungry. Bartley took him to dinner and paid for it with his (Willy’s) own money. Willy ate unhappily after signing for the advance.

The bus was in bad enough shape that Wednesday’s gig was in jeopardy. Bartley looked worried. He called Leon, who was sympathetic and said his band would fill in if necessary.

***

By 9:00 AM the weather had eased up enough so we were able to walk to town and find a restaurant. Bartley made some calls and before long a truck came and towed us to a garage. They wouldn’t work on Sunday, so we were stuck there at least a day. Bartley got a key to a side door so we could come and go but everything around the garage was closed and it was too cold to go far.

Everyone seemed to be taking the confinement in stride. Artie worked on a chart (his writing and copying were better than his playing), the others just sat around. Willy tried to push the “Coffee--Black” button on a vending machine, but his hand was too unsteady. He asked for help, but Bartley grabbed his hand--like catching a hummingbird--and with Willy’s bony index finger pushed the chicken soup button instead.

“The power of suggestion,” Bartley said.

Downtown Wichita may not be half as exciting as everyone thinks but it sure beats starving to death in a freezing garage. Lee, Artie and I went to a restaurant where Artie asked the waitress to quit her job and run away with him.

Richard made quite a hit with the mechanics. They laughed at everything he said and at his splayfooted, arm-swinging walk. They saw him as part Charlie Chaplin, part Huntz Hall. He loved the attention. He voiced one inanity after another and walked back and forth to the unending glee of the men. Finally Bartley, fearing the bus would never get fixed, ordered him to his seat. That lasted about five minutes.

Willy asked Bartley for a draw (an advance on his salary). Bartley asked why he needed the money. Willy said he was hungry. Bartley took him to dinner and paid for it with his (Willy’s) own money. Willy ate unhappily after signing for the advance.

The bus was in bad enough shape that Wednesday’s gig was in jeopardy. Bartley looked worried. He called Leon, who was sympathetic and said his band would fill in if necessary.

***

We got back in plenty of time for the gig. Susan got sick during the second set and Bartley drove her to their hotel. We played the last two sets without a bass.

The next day, Susan was still not able to work so Bartley hired Joan Hooker, Don’s wife, for the gig in Ponca City. Joan is a dancer who quit working full time to get married. She still works occasionally, if the situation is right. She’s really nice and unaffected, considering how good-looking she is. She and Don live in an apartment just south of downtown. They took their own car to Ponca City. All of us wished we could ride with them, but no one asked and they didn’t offer.

Artie went wild when he met Joan. Oblivious to Don’s scowl, he wouldn’t leave her alone. At first she pretended not to notice but when that was no longer possible she told him to get lost. Seething, Artie lost all concentration and played a lot of wrong notes and rhythms. Bartley got angry and kept us on the stand for nearly and hour and a half, twice the normal set and when he did let us off it was only because the crowd needed a break.

Artie has mastered the road. Everything he owns, except his trumpet, is in one small suitcase. He almost never wears anything but the same greenish wool suit, sometimes with a white shirt and tie, but it always looks pressed. How does he do that? He can give himself his insulin shot on the bumpy bus and not draw blood. He writes good arrangements and copies them while the bus is limping along and it looks like a printing press did the work. He’s not a bad guy, but it can be difficult to be around him when there is a female present.

The show was a disaster and instead of the short intermission that usually follows it, Bartley went right into a dance set, called up the longest charts in the book and kept us on the stand another hour and a half.

No one has mentioned New York lately. Is this band really going to New York?

***

The next day, Susan was still not able to work so Bartley hired Joan Hooker, Don’s wife, for the gig in Ponca City. Joan is a dancer who quit working full time to get married. She still works occasionally, if the situation is right. She’s really nice and unaffected, considering how good-looking she is. She and Don live in an apartment just south of downtown. They took their own car to Ponca City. All of us wished we could ride with them, but no one asked and they didn’t offer.

Artie went wild when he met Joan. Oblivious to Don’s scowl, he wouldn’t leave her alone. At first she pretended not to notice but when that was no longer possible she told him to get lost. Seething, Artie lost all concentration and played a lot of wrong notes and rhythms. Bartley got angry and kept us on the stand for nearly and hour and a half, twice the normal set and when he did let us off it was only because the crowd needed a break.

Artie has mastered the road. Everything he owns, except his trumpet, is in one small suitcase. He almost never wears anything but the same greenish wool suit, sometimes with a white shirt and tie, but it always looks pressed. How does he do that? He can give himself his insulin shot on the bumpy bus and not draw blood. He writes good arrangements and copies them while the bus is limping along and it looks like a printing press did the work. He’s not a bad guy, but it can be difficult to be around him when there is a female present.

The show was a disaster and instead of the short intermission that usually follows it, Bartley went right into a dance set, called up the longest charts in the book and kept us on the stand another hour and a half.

No one has mentioned New York lately. Is this band really going to New York?

***

Ronnie Bartley Band salaries:

$100: Richard Stevens, Don Hooker

$85: Lee Naasz, Harold Boyce

$75: Art Athey, me.

$65: Willy Coleman

$50. Mary Sue Crouch aka Susan Gray

Willy staggered in ten minutes late, wearing a wrinkled pair of black cotton pants. He said he lost his tux pants. Later, he discovered he was wearing them underneath the cotton ones.

After the gig, on the bus to Laredo, Bartley was unusually jovial. “Welcome to the annual Ronnie Bartley Band Picnic,” he said and began to open packages of white bread and baloney and a jar of mayonnaise.

The gig in Laredo is on Saturday but Bartley wanted to get there Friday so we could take advantage of the cultural opportunities available in Nuevo Laredo, just across the border.

Artie and Richard spent the evening in Nuevo Laredo and came back with stories about their new girlfriends. Artie’s is named Letecia. They will be married as soon as she returns from a visit to her mother in Matamoros. Richard’s fiancée is named Rosie and she laughs at everything he says.

Returning to the US they were stopped by border guards in a routine check. Artie was waved through, but when Richard gave his birthplace as “Sahnf-Ceesco” (when in Rome, etc., and everyone around there seemed to have an accent), he was taken to an interrogation room, stripped, searched and questioned. Artie, who at first considered leaving him there, finally convinced him to drop the accent and he was released.

Meanwhile, Lee and Harold had a mission. They had developed a sudden need for Benzedrine and with Mexico so close...

Right after noon the two of them and I (an unwitting co-conspirator) crossed the bridge to Nuevo Laredo. In order to throw the feds off the track we ate at a taco stand and browsed in some shops. Then we went into a drug store where they bought a can of talcum powder and a hundred bennies. We walked a couple of blocks to a hotel and into a restroom off the lobby. While Lee leaned against the door, Harold pried the can apart at a seam and poured some of the powder onto a paper towel. He put the pills into the can and replaced the powder and the top of the can, not perfectly, but well enough. He said his charm and his ability to remain calm under fire would get us safely across the border.

At the border, the guard waved us through without looking up.

$100: Richard Stevens, Don Hooker

$85: Lee Naasz, Harold Boyce

$75: Art Athey, me.

$65: Willy Coleman

$50. Mary Sue Crouch aka Susan Gray

Willy staggered in ten minutes late, wearing a wrinkled pair of black cotton pants. He said he lost his tux pants. Later, he discovered he was wearing them underneath the cotton ones.

After the gig, on the bus to Laredo, Bartley was unusually jovial. “Welcome to the annual Ronnie Bartley Band Picnic,” he said and began to open packages of white bread and baloney and a jar of mayonnaise.

The gig in Laredo is on Saturday but Bartley wanted to get there Friday so we could take advantage of the cultural opportunities available in Nuevo Laredo, just across the border.

Artie and Richard spent the evening in Nuevo Laredo and came back with stories about their new girlfriends. Artie’s is named Letecia. They will be married as soon as she returns from a visit to her mother in Matamoros. Richard’s fiancée is named Rosie and she laughs at everything he says.

Returning to the US they were stopped by border guards in a routine check. Artie was waved through, but when Richard gave his birthplace as “Sahnf-Ceesco” (when in Rome, etc., and everyone around there seemed to have an accent), he was taken to an interrogation room, stripped, searched and questioned. Artie, who at first considered leaving him there, finally convinced him to drop the accent and he was released.

Meanwhile, Lee and Harold had a mission. They had developed a sudden need for Benzedrine and with Mexico so close...

Right after noon the two of them and I (an unwitting co-conspirator) crossed the bridge to Nuevo Laredo. In order to throw the feds off the track we ate at a taco stand and browsed in some shops. Then we went into a drug store where they bought a can of talcum powder and a hundred bennies. We walked a couple of blocks to a hotel and into a restroom off the lobby. While Lee leaned against the door, Harold pried the can apart at a seam and poured some of the powder onto a paper towel. He put the pills into the can and replaced the powder and the top of the can, not perfectly, but well enough. He said his charm and his ability to remain calm under fire would get us safely across the border.

At the border, the guard waved us through without looking up.

Artie and Richard went shopping for presents for their fiancées. Artie couldn’t find anything suitable but Richard bought Rosie a red dress, a little too large, perhaps, but a steal at only $8. Besides, the saleswoman said, in English better than his, it could easily be taken in a little.

Back at the border, Richard was again detained, searched and questioned. (I wonder what’s so suspicious about a blond guy speaking Pidgin English and carrying a large red dress?) Artie lost all patience and began to scream at Richard until the guards threatened to arrest him if he didn’t leave.

“They got him again,” he shouted as he raced past us on his way to find Bartley.

After the gig, a friend of Harold’s, an Air Force lieutenant, drove us across the border to a nightclub where a fantastic magician was working. After his act the little house band played the exit music, a Sonny Rollins tune called Doxy. The trumpet player took a solo then put his horn on top of the piano and walked off toward the bar. The tenor player began to play. Artie went to the front of the bandstand and stood there listening. When the tenor player finished, Artie picked up the trumpet and began to play, clipped two and three note phrases that bore little relationship to the simple chord changes. The trumpet player ran in from the bar and stood looking angry and a little afraid. After a few choruses, Artie put the trumpet back on the piano and jumped triumphantly from the stage. The band quit immediately and began to pack up.

“That’s an unusual style,” I said to Artie.

He stood with his fists on his hips and stared at me. “I play like Miles Davis,” he snarled.

Near the border Harold tried to coach Richard in how to outwit the treacherous guards.

Why not tell them you’re from Oakland?” he asked.

“Because I’m not.”

“Where are you from?”

“San Francisco.”

“Well, why don’t you say San Francisco?”

“Because they won’t understand me.”

“Yeah, but they’ll know you’re a gringo; they’ll have to let you through.

Richard remembered the cold concrete detention room, the order to strip, the demeaning search for drugs, the questions, the wait until Bartley could be found to gain his release. And it was late and he was tired.

At the guard station, Artie, still fuming, went first, followed by Lee, Harold, Harold’s friend and me. Then it was Richard’s turn.

“Birthplace?”

“Sahnf-ceesco.”

The guard grinned and waved him through.

Back at the border, Richard was again detained, searched and questioned. (I wonder what’s so suspicious about a blond guy speaking Pidgin English and carrying a large red dress?) Artie lost all patience and began to scream at Richard until the guards threatened to arrest him if he didn’t leave.

“They got him again,” he shouted as he raced past us on his way to find Bartley.

After the gig, a friend of Harold’s, an Air Force lieutenant, drove us across the border to a nightclub where a fantastic magician was working. After his act the little house band played the exit music, a Sonny Rollins tune called Doxy. The trumpet player took a solo then put his horn on top of the piano and walked off toward the bar. The tenor player began to play. Artie went to the front of the bandstand and stood there listening. When the tenor player finished, Artie picked up the trumpet and began to play, clipped two and three note phrases that bore little relationship to the simple chord changes. The trumpet player ran in from the bar and stood looking angry and a little afraid. After a few choruses, Artie put the trumpet back on the piano and jumped triumphantly from the stage. The band quit immediately and began to pack up.

“That’s an unusual style,” I said to Artie.

He stood with his fists on his hips and stared at me. “I play like Miles Davis,” he snarled.

Near the border Harold tried to coach Richard in how to outwit the treacherous guards.

Why not tell them you’re from Oakland?” he asked.

“Because I’m not.”

“Where are you from?”

“San Francisco.”

“Well, why don’t you say San Francisco?”

“Because they won’t understand me.”

“Yeah, but they’ll know you’re a gringo; they’ll have to let you through.

Richard remembered the cold concrete detention room, the order to strip, the demeaning search for drugs, the questions, the wait until Bartley could be found to gain his release. And it was late and he was tired.

At the guard station, Artie, still fuming, went first, followed by Lee, Harold, Harold’s friend and me. Then it was Richard’s turn.

“Birthplace?”

“Sahnf-ceesco.”

The guard grinned and waved him through.

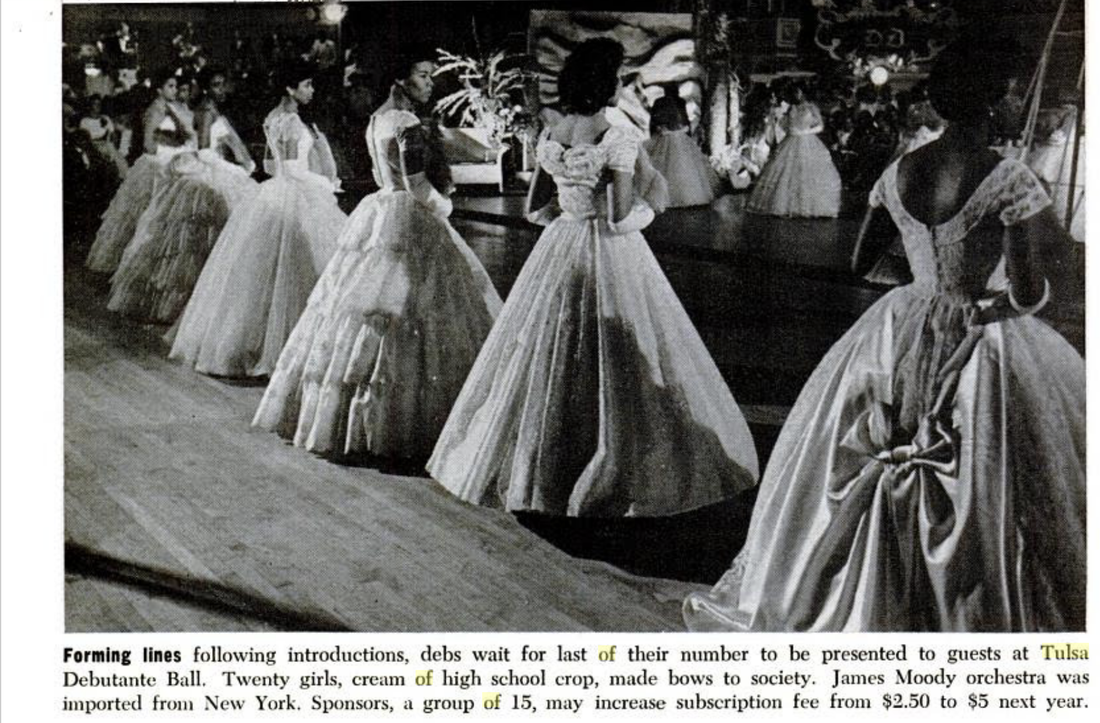

Separate but Equal: The white waiting room at the Greyhound Station is indoors. Black folks get to do their waiting outside in the cold, fresh air.

I went to the ballroom to practice but Leon’s band was setting up to rehearse. They have a new drummer, Van Proudfoot, and I talked to him for a few minutes. Van is from Omaha and this is his first steady gig. If it doesn’t work out, he says, he’ll go to Arizona and be a salesman. That night, I went to Walgreens for dinner and he was there. I talked to him for a while but he’s not real interesting.

I passed the Denver on the way back to the Eagle and saw Richard and Harold at the counter. I went inside. An old woman, one of the regulars, was there drinking coffee. Sometimes she glides back and forth between the counter and the tables, clapping her hands and reciting rhymes in a language all her own. Sometimes she would brace herself between two seats and pedal her feet in the air, the way Richard does.

Richard was concerned about the Benzedrine. Harold pointed out that we were in a public place and asked to defer the discussion. Richard persisted. “It’s against the law,” he said.

“Those pills are medicine,” said Harold, “and truck drivers use them all the time.”

“We’re not truck drivers,” said Richard.

“No, we’re not,” said Harold, “but I drive the bus and I wouldn’t want to crash and get everybody killed.”

***

We left at 3:00 for the hundred-mile trip to Coffeyville. The bus ran smoothly and we got there in plenty of time for a leisurely dinner. The restaurant was a cousin of the Denver Cafe. I had the chicken fried steak, a dollar-ten. The dollar was for atmosphere.

Susan had on a new silver dress. I prefer it to the gold one.

***

A lodge hall in Pittsburg, Kansas, on the fifth anniversary of the death of Charlie Parker. I was alone in the restroom and started to write “Bird Lives” on the mirror with soap but I heard the outer door open and had to stop. I wonder if anyone else in the place even knew who Bird was? Except us, of course. Well, some of us anyway.

***

On the way out of town we ran into an honest-to-god traffic jam, the first since I had left LA. Richard had the solution and it’s so simple I wonder why no one ever thought of it before. “I think the cars in front should go faster,” he said.

***

Memphis. The electric sign on the bank said 29º.

Separate but Equal: The white waiting room at the Greyhound Station is indoors. Black folks get to do their waiting outside in the cold, fresh air.

***

I passed the Denver on the way back to the Eagle and saw Richard and Harold at the counter. I went inside. An old woman, one of the regulars, was there drinking coffee. Sometimes she glides back and forth between the counter and the tables, clapping her hands and reciting rhymes in a language all her own. Sometimes she would brace herself between two seats and pedal her feet in the air, the way Richard does.

Richard was concerned about the Benzedrine. Harold pointed out that we were in a public place and asked to defer the discussion. Richard persisted. “It’s against the law,” he said.

“Those pills are medicine,” said Harold, “and truck drivers use them all the time.”

“We’re not truck drivers,” said Richard.

“No, we’re not,” said Harold, “but I drive the bus and I wouldn’t want to crash and get everybody killed.”

***

We left at 3:00 for the hundred-mile trip to Coffeyville. The bus ran smoothly and we got there in plenty of time for a leisurely dinner. The restaurant was a cousin of the Denver Cafe. I had the chicken fried steak, a dollar-ten. The dollar was for atmosphere.

Susan had on a new silver dress. I prefer it to the gold one.

***

A lodge hall in Pittsburg, Kansas, on the fifth anniversary of the death of Charlie Parker. I was alone in the restroom and started to write “Bird Lives” on the mirror with soap but I heard the outer door open and had to stop. I wonder if anyone else in the place even knew who Bird was? Except us, of course. Well, some of us anyway.

***

On the way out of town we ran into an honest-to-god traffic jam, the first since I had left LA. Richard had the solution and it’s so simple I wonder why no one ever thought of it before. “I think the cars in front should go faster,” he said.

***

Memphis. The electric sign on the bank said 29º.

Separate but Equal: The white waiting room at the Greyhound Station is indoors. Black folks get to do their waiting outside in the cold, fresh air.

***

Bartley hasn’t said anything about New York lately and no one has asked. We should be hearing soon, shouldn’t we? After all, we’ll be gone for a month, which will take more preparation than one of our weekend trips.

Letter from home: The Dobkins know a family in Tulsa named Pollack. I’ll call them when we get back from New Mexico next week. Maybe they’ll invite me for Passover.

***

Near Roswell at a place called Tyler’s Inn. The Tylers are the people who took the Bartleys out the last time we were here. We’re Mr. Tyler’s favorite band and Susan is his favorite singer and bass player. He stares at her, hovers around her and compliments her singing and playing and her looks. His wife just sort of grins.

Susan likes them too and their restaurant, particularly their salad dressing; she talked about it all the way here. I tried it. It’s awful. It tastes as if they use lemon juice instead of vinegar.

“They use lemon juice instead of vinegar,” said Susan. She couldn’t be happier. I could; the creep charged us full price for dinner.

The gig was actually fun for a change. The crowd loved us almost as much as Tyler did, and they were so noisy we couldn’t hear Susan or Willy. Bartley called up more than the usual number of jazz charts and everyone really dug in, but nothing could erase the memory of that miserable meal at a king’s ransom $3.25.

***